Glucotrack (Nasdaq:GCTK) believes it can tap into a diabetes market that includes millions of people who aren’t being served completely.

That’s according to the company’s Chief Scientific Officer, Mark Tapsak, who gave a presentation on the company’s long-term implantable continuous blood glucose monitor (CBGM) as part of the American Diabetes Association’s 85th Scientific Sessions’ “Innovation Hub.”

Rutherford, New Jersey-based Glucotrack is looking to enter the fiercely competitive continuous glucose monitor (CGM) market, but with something different from the options out there. The likes of Abbott and Dexcom lead the way with minimally invasive devices that measure interstitial fluid over a wear time of around a couple of weeks, depending on the device. Senseonics is the most similar in the sense that it is implantable, with its Eversense 365 lasting for one year.

However, Glucotrack believes it has something unique to offer.

Earlier this year, the company completed the first-in-human study of the system. Now, it expects FDA investigational device exemption (IDE) in the fourth quarter of 2025. The study would likely help the company work toward a submission to bring the device to market in the U.S. down the line.

“We really want to redefine continuous glucose monitoring with the implantable long-term system,” Tapsak declared.

What is the GlucoTrack device?

Glucotrack’s device features no on-body external component. The company designed it for three years of continuous, accurate blood glucose monitoring for a more convenient, less intrusive solution.

Unlike traditional CGMs that measure glucose in interstitial fluid, the CBGM measures glucose levels directly from the blood. It aims to provide real-time readings without the lag time typically associated with interstitial glucose measurements.

According to Tapsak, many of the company’s leadership bring experience from the more traditional CGM makers.

“These are great products,” he said. “They’re wonderfully accurate products and I think they have literally changed the way that people with diabetes are managing their care. But, we think there’s still some unmet need.”

Related: FastWave Medical reports first-in-human use of coronary laser IVL system

Tapsak believes Glucotrack’s device taps into the convenience factor with the elimination of an on-body device. Users don’t have to worry about wearing it while swimming or exercising, or dealing with adhesives that break free. He said those issues linger on the minds of those with diabetes, and Glucotrack’s offering can change that.

The implant goes five centimeters within the subclavian vein. Glucotrack’s active implantable device has a small battery and some electronics that go just under the skin in the pectoral region. Tapsak explained that the location of the implant is not in a major vessel, but the implant can measure real-time glucose levels as pulsatile blood flows over the tip of the sensor.

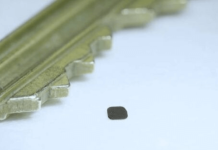

About the size of a USB drive, the device weighs just 6.5 grams.

According to Tapsak, Glucotrack’s device avoids certain challenges that come with working in the interstitial space. Those include lag times in readings, compression lows and more.

“It’s different,” Tapsak said of the company’s implant location. “It’s a protected space.”

Like a pacemaker

According to Tapsak, a survey conducted by DQ&A, an insights partner aiming to drive more confident diabetes decision-making, highlighted certain challenges with CGM. In 2018, the survey reflected desire for longer sensor wear time, shorter warm up time, better accuracy and longer transmission distance. In 2024, nearly 3,000 respondents continued to say that existing CGMs failed to meet these needs.

“This becomes our motivation,” Tapsak said. “To have a set it and forget it-style meter.”

He likened the device to a cardiac loop recorder, or pacemaker, a very commonly implanted device. Essentially, interventional cardiologists already know how to implant those — meaning they don’t require education on the Glucotrack device. It requires the same access, the same type of insertion and goes in a similar pocket of the body.

“What we’re taking is what we would consider to be very well-known, proven technologies, implant techniques, materials, construction technologies and fabrication,” Tapsak explained.

Glucotrack uses “gen-one” glucose sensor chemistry, or glucose-oxidase-based chemistry. The company placed its sensor on the electrodes and the final device, with a predicted three-year longevity, connects with a smartphone using Bluetooth connectivity. The diameter of the device comes in at just about 1.3 millimeters. With all this considered, the company believes it can achieve the required safety levels to bring the device to people with diabetes.

“Probably the closest predicate device is a pacemaker,” Tapsak said. “We don’t go in as aggressively, even compared to a pacemaker, so already complications are in that 1% or lower range. … It doesn’t go far into the vasculature.

“We have that insertion point that goes in right in then vessel, then it’s the tip that’s actually doing the sensing in the blood flow. It’s sort of free-floating in the blood stream.”

What’s next?

Tapsak said a survey from two years ago asked 757 patients if they were likely to acquire a CBGM based on two-year longevity. Even though the company has since expanded its expectation to three years, the point remains that the survey gauged interest in the device. Glucotrack had more than 50% of respondents say they’d be “likely or extremely likely” to adopt a two year implant.

According to Tapsak, using DQ&A correction factors, about 17% of those surveyed would realistically be open to it.

“We really feel that this particular solution is something that people want,” he said. “The motivation is to make this as set-it-and-forget-it as possible. … I want to make this as easy as possible for the user experience.”

Glucotrack that first-in-human study earlier this year and now plans to launch a new study in the next month. The company also expects to enroll five patients in Australia within the month for a one-year study, then bring a study to the U.S. at the beginning of next year.

To round it out, Tapsak says the company expects to begin a pivotal trial by the end of 2026, potentially putting it on the path to bring this three-year implant to the diabetes community.

“By removing some of that burden of the wearables, the inventory, some of that hassle factor, both from the patient and the clinical perspective, we hope to help a lot of people manage their disease and improve their quality of life,” Tapsak concluded.